What is Structured Word Inquiry?

Structured Word Inquiry (Bowers and Kirby, 2010) is a way of working with language to show that spelling makes sense. In fact, our spelling system is so logical and well-ordered that it can be investigated and understood through scientific inquiry.

We all know that “sound it out” only works part of the time. This means that it is not a reliable method for determining the spelling of a word. Instead, when using SWI, we start by asking, “What does the word mean?”

Homophone pairs are some of the words that make us think English is a confusing and frustrating language to spell. If we start by thinking about what a word means, we may find that we already have the information we need to understand a spelling. I recently came across the homophone pair ‘discussed’ and ‘disgust.’ Let’s see if meaning can help us understand the spelling of these words.

Homophone pairs are some of the words that make us think English is a confusing and frustrating language to spell. If we start by thinking about what a word means, we may find that we already have the information we need to understand a spelling. I recently came across the homophone pair ‘discussed’ and ‘disgust.’ Let’s see if meaning can help us understand the spelling of these words.

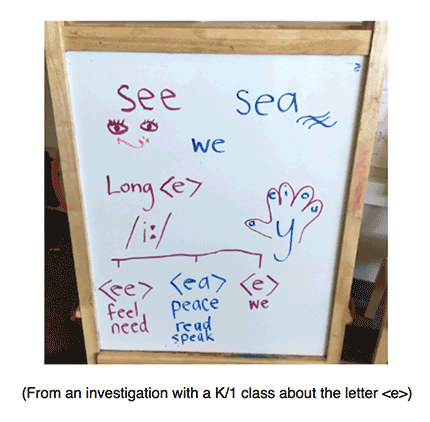

The word ‘discussed’ is the past tense of ‘discuss’ and so it takes the <-ed> suffix. (It can also act as an adjective, so it is formally called a ‘past participle.’) In SWI we use a tool called the ‘orthographic word sum’ to model the structure of a word. So far, we have evidence for:

< discuss + ed –> discussed >

Now we can ask, “What does ‘discuss’ mean?” In present day it refers to people talking together, sharing ideas, thoughts, or beliefs. A discussion can be heated, or it can be a way of clarifying and sharing one’s own thinking, such as in a book group discussion.

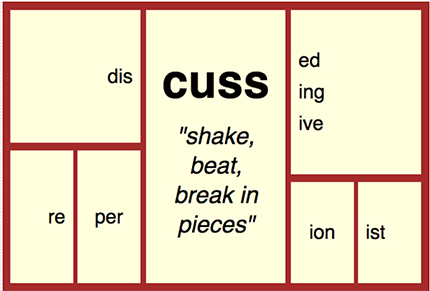

If we look into a word’s history, or etymology, we can find out even more about the word’s structure. The word is derived from the Latin discutere/discussum (itself derived from quatere/quassum), which had the sense and meaning of “to shake, beat, break in pieces.” Later in Latin it developed the sense of “investigate, examine.” We can see the echoes of our present day English base element . Now we have evidence for:

I love that ‘percussion’ also evolved from the same Latin root. A discussion with a percussionist might be ear shattering indeed.

(Incidentally, this ‘bound base’ is not related to the free base word ‘cuss’, which is actually a relative of ‘curse.’ They are homographs.)

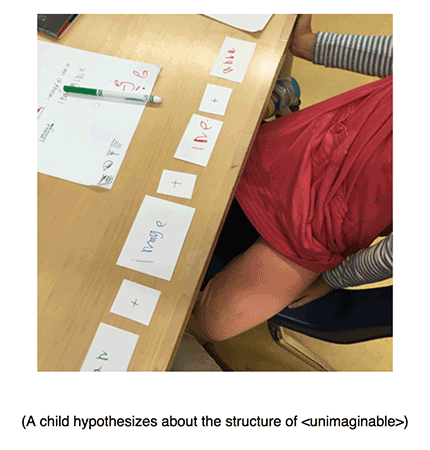

When students consistently investigate the structure of words, they come across certain morphemes frequently, such as prefixes and suffixes. Over time, these morphemes stand out when they come to an unfamiliar word. Being able to use meaningful structures to investigate a word puts a student on a faster track to understanding.

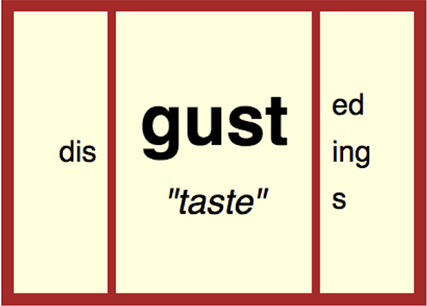

Speaking of being tuned in to structure, if we return to the other word in our homophone pair, <disgust>, we may recognize a possible prefix right away. We could propose a hypothesis for the word’s structure:

dis + gust –> disgust

In order to support this hypothesis, we can look into this word’s history and evolution to learn more. The word ‘disgust’ came through French from the Latin root gustare meaning “to taste.” The <gust> in the root gives us evidence for our present day structure, so now we also have a deeper insight into the word’s meaning. The <dis-> prefix in this case represents the sense of “opposite of, reversal,” so ‘disgust’ literally means “having a distaste.” We can see how this applies to our current sense and meaning of “revulsion or disapproval.”

This family includes familiar forms like <disgusting, disgusted, disgusts> and it also includes an Italian loan word, ‘gusto’ meaning “taste.” Metaphorically we can imagine that when someone does something ‘with gusto’, they have a fond taste for it, which leads them forth with enjoyment or zest.

When we look under the surface at the meanings of these words, we can see their structure. When we understand their structure, it becomes clear why the words are spelled the way they are. Now we have evidence that helps us understand why we can’t say English spelling is phonetic. Our spelling represents its meaningful structures before pronunciation. A language that takes both of these systems into account is called ‘morphophonemic.’ The nature of English is that it follows this morphophonemic principle.

An investigation like the one above is what Structured Word Inquiry does. It supports learning through understanding rather than memorization and drill. When we understand something, we experience those “light bulb” moments, and feelings of satisfaction, pride, and inspiration can rush over us. That’s certainly how I have experienced it, and I’ve seen the same in the students I’ve worked with. (Children and adults!)

SWI is not a program with a fixed scope and sequence. The term represents a method for using what is true about our language to understand it better. Instructional practices are left up to the teacher or tutor, as long as they support the accurate science of language. Any word that provokes curiosity or interest in a student is a good one to begin with. One of the first words I worked with was ‘grandiloquent’ because a first grader heard it and wanted to know more about it. Boy, did we learn a lot with that one.

In most classrooms, students are confronted with a list of 10 – 20 unconnected words, which happen to share some common phonic feature, and they are asked to memorize their spellings. Instead, through SWI we work with a set of words that share a meaningful base element to make deep connections. The deeper the understanding, the more likely students are to remember what they’ve studied.

Most importantly, using inquiry to build one’s own understanding is exciting and joyful. It summons our intellect and moves us to keep learning and growing. As my colleague Gina Cooke says, we know stories are made of words, but let’s also remember that every word tells a story. And who doesn’t enjoy a good story?

To Get Started Working with Me