14 Dec The Base + ic + s

I recently did a lesson with a class of 3rd and 4th graders, whom I visit once a week. This was only their second lesson with Structured Word Inquiry. I knew I wanted to keep the words we used fairly simple so that they could understand the orthographic concepts and terminology we use when talking about a morphological word family. I told them we would play “All About That Base,” which immediately prompted a laugh and a discussion about the homophones <base> and <bass>. It was a rainy day, so I chose to put these words on the board: rainy, rained, raincoat, rainier, and rainiest.

I explained that every word has a base or is a base, and that the base is what holds the meaning of the word. I had them hold out their fists to represent a base element and repeat, “The base holds the meaning!” (For more on this see this post.) Then I pointed to the words on the board, read them aloud, and asked, “What might be the base for this family of words on the board? What do all these words share in both their spelling and their meaning? What do they have in common?”

I gave them some think time, but I had an assumption that the answer would be obvious to them. After all, this was a typical class of bright 9 and 10 year-olds, and I had put out the question several ways using common language as well as the orthographic terms. Interestingly the suggestions for the base were:

<rain>

<rainy> or <rained>

<ra>

<ie> (They noted only some of the words had this sequence.)

Needless to say I was pretty much floored by their general inability to see that all these words shared the free base element <rain>. Only one student out of 12 realized this, and even though she was the first one to share, no one else jumped on board.

Learning via a traditional phonics model conditions us very early on to disregard meaning and look primarily for sound represented in the spelling. Unfortunately, that’s just not how English orthography works. Science shows us that English spelling is primarily based on meaning. We next consider the word’s history (etymology), and pronunciation is the final consideration.

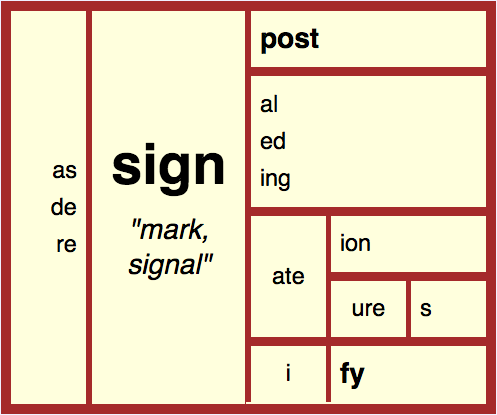

Think about the word <sign>. You’ve probably just memorized its spelling and forgotten about that surprising <g>. If we take a moment to wonder about it, we should start with the meaning of the word. What is a sign? It’s some kind of signal to let us know something important, like a traffic sign. Or even a traffic signal.

Did you see what happened there? The definition brought in another member of the family: <signal>. If we do some research, we will find out that the words <sign, signal, signature> all come from a shared Latin root, signum, with the sense and meaning of “a mark, sign.” So the word <sign> must keep that <g> to show that it is a member of this morphological family. That overrules the need to have a one-to-one sound/symbol correspondence. Without the historical <g> we would be left with <sin> which wouldn’t work for a couple of obvious reasons, or <sine> which is also already a word. Or maybe <*sighn>? The grapheme <igh> is not typical of words of Latin origin.

If we know how the language works, we can see that it’s actually working for us and not against us. The spelling is preventing confusion with other words and meanings. But we can only appreciate the clues along this path if we understand that phonology comes last, not first.

The students that I see learning about morphology in kindergarten, or even pre-kindergarten, automatically have meaning at the forefront of their investigations. They would have quickly called out the connection to <rain> because their minds are trained to analyze for meaningful connections first. Only if we understand the meaning of a word can we understand its spelling.

This is a gift we can give every student, and we can do it easily. Words are built with bases and affixes, and bases hold the meaning of words. Building up a repertoire of common prefixes and suffixes allows students to see the structure of words more easily. The spelling of a word is contained within the structure. Revealing a base element also provides an opportunity to see (often surprising) connections to other words in the family. And watching the lights turn on for students when they build this kind of understanding is nothing short of joyous.