23 Feb Engaging Curiosity

This is the first post in my series called “First Steps,” which is intended for anyone just beginning their journey with Structured Word Inquiry. Since SWI is not a program, people can feel very nervous about where to start. You are told there is no ideal order of words or concepts to teach, and no scope and sequence of essential concepts by grade level. Eventually you’ll find this exciting and freeing, but when you start out it feels like jumping off a cliff without a net.

I have heard teachers and tutors asking for guidance around the same themes as they begin. I’m hoping this series will give you a bit of comfort along your way.

Step One: Engaging Curiosity

Children are born curious, but once we start “instructing” them about spelling their curiosity can begin to fade. They wait to be told how spelling works and dutifully apply the lessons they’ve learned to the best of their ability. Unfortunately the information provided in these lessons is usually missing some crucial elements. Some students appear to do fine anyway, but the students for whom it doesn’t work begin to slip into frustration. If a teacher can’t help them understand spelling, who can?

What if, though, instead of just sitting with the frustration, children knew that they could ask for more information? If the spelling of <does> seems weird, it warrants an investigation. The same goes for a juicy word like ‘polytheism’ found in a study of Ancient Egypt.

When I first began, I felt the same worry you might be feeling about starting with the right words so that I could be sure I was hitting all the important concepts. Even though I had mentors who told me not to worry, that the most important concepts would come up on their own, I had to experience it for myself.

As I experimented, I found that when I chose words for students based on their errors, the students were less invested in the lesson. This was particularly true when I was just beginning to learn more about orthography. Students were more patient with me stumbling around on Etymonline, sifting through new information when they were truly interested in the word.

Also, the kids often chose complex words, which were inevitably more interesting than the simple words I wanted them to work on. (Thanks to Gina Cooke’s Insight Decks we can all understand more about those words, too!)

For the past few years, I have been part of a community that embraced SWI school wide. The wonderful thing about this school is that inquiry and questioning are already a part of their culture. Curiosity is nurtured and valued. I have been able to watch the students’ behaviors shift to include language as part of their raw material for exploration and investigation. The teachers honor the questions that come up, even if they don’t know how to answer them.

Now that I am the school’s SWI coach, I have kids coming up to me all the time with wonders. The flood of desire to understand (and/or challenge their teacher!) just can’t be squelched.

One day in the first grade as I was about to start a lesson, a boy raised his hand to ask, “How can the <o> in ‘gold’ say its name when there’s no <e> at the end of the word?” He continued, “I saw the word on our lotion bottle and I brought it in. Let me go get it from my locker.” Lo and behold, out of his backpack came the bottle of Gold Bond lotion, which he cared enough about to bring to school. Discussions started to bubble up amongst the students. That provided the inspiration for the following week’s lesson.

Another day, I had just arrived at school via the playground, and a first grade girl ran up to me with bright eyes.

“Rebecca, I have a question for you! Why is there a <b> at the end of ‘comb’?”

Keep in mind, this child interrupted what she was doing during her recess to come talk to me about words. I replied,

“Well, that’s interesting. Remember if there’s a letter in a word and we don’t pronounce it, we need to check out the word’s history.”

She thought for a moment and said, “So maybe it’s because it came from Old English and it used to be spelled that way?”

What a hypothesis! When I asked if she wanted me to come by later to check it out, her eyes lit up, and she nodded enthusiastically. I returned during her afternoon recess, and a small group of children ended up huddled around us to join in the discovery. During recess. When has that ever happened with a traditional spelling lesson?

What about schools that take a more structured approach to their curriculum in general? Can curiosity be reignited there, too?

Once a week I visit a 3rd/4th grade class at a different school. Their literacy instruction is based on a traditional phonics program. Imagine the discomfort these students felt when I brought in new ideas that dumped phonics on its head. They were not excited. They wanted to stick with their online program that told them what to do, mostly because they were used to it, not necessarily because it was working. This was surprising to me because everyone else up to that point had been totally taken with SWI.

It took several sessions for me to find what would engage these students. It also took collaboration with their lead teacher, who was not yet convinced about SWI. My first successful entry point happened when I brought out a copy of the Greek alphabet. The students were studying classical civilizations, and they loved puzzling through how Greek might be translated into English. Looking at a different alphabet took away their usual feelings about English spelling. It allowed for a chink in the armor of their general frustration with language.

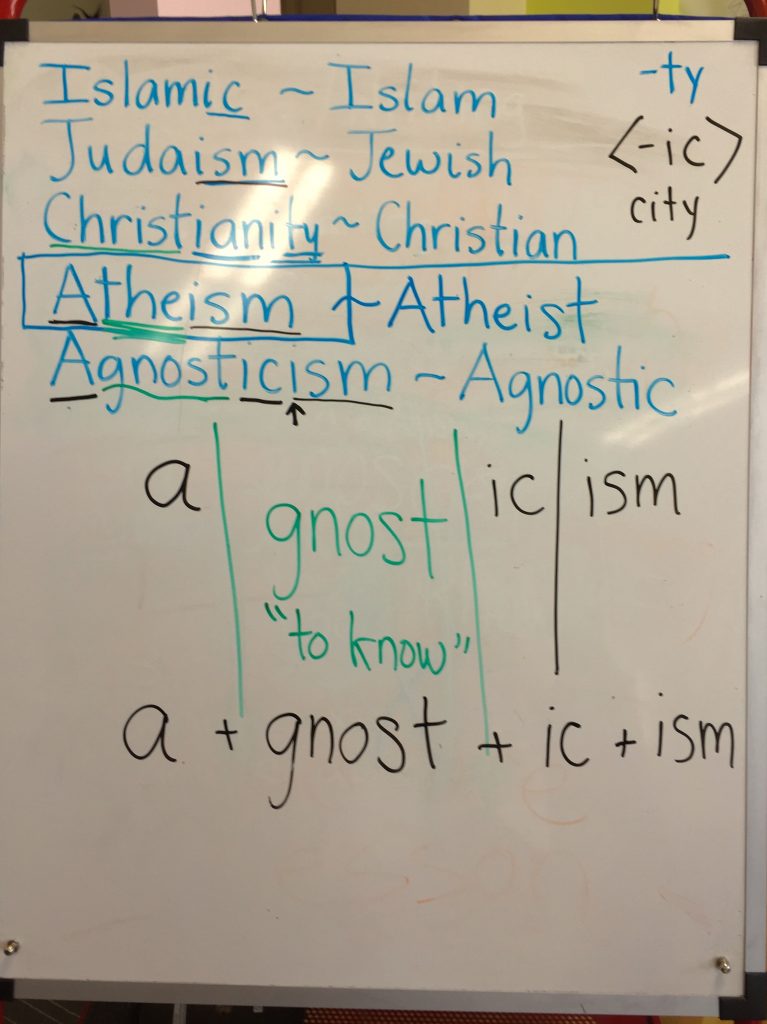

A few weeks later I had the fortune of being able to listen in to a deep class discussion about politics and religion. The words ‘Islamic, Judaism, Atheism, Agnostic, Christian, and Christianity’ provided the foreground for some big aha’s about how the structure (morphology) of language works. I led the students through considering how some of the related words were built. ‘Christianity’ has a <Christian> inside it. Who is it that ‘Christians’ worship? Jesus ‘Christ.’ Then a student pointed out that it’s because of him we celebrate ‘Christmas.’ Suffixes and prefixes started popping off the board for them, and the meaning of the base elements provided the illumination they had been previously unable to see.

I wanted proof that they were engaging with this material. Last week I started off their lesson with a few general statements to fill in, such as: “When we investigate a word, we know that the ________ holds the key to the meaning.” Immediately kids shouted out and raised hands: “Base!”

As I wrapped up the lesson, I had students coming up to me saying things like,

“When you first started coming I thought word study was so boring, and I couldn’t wait for it to end. But now I don’t want to stop. I could just keep talking and talking about words!”

“My brain is so much bigger now. I can feel it getting bigger every time we study a word!”

“I love this class!”

Now they keep a list for me with words they want to take on, like ‘tsunami, vertebrae, element, realm, and integrity.’ Do these students still have a lot of misunderstandings about spelling? Absolutely. But now they are seeking meaning on their own, and that is what will transform them, not my attempts to “fix” their spelling.

Once students have experienced the joy of the quest, I find they don’t mind shifting to look at the errors in their spelling. They might even bring up those words on their own.

You are now free to choose any word that will engage the curiosity of your student or students. What is your class studying? What interesting words can be found in your class read aloud? What is your tutoring student interested in? Make a list of words that come to mind, or ask your student to talk about things they like. Listen carefully to what they say. Listen for verbs, especially verbs that are also used as nouns like ‘run’ or ‘move.’ These types of words often have big families, which is fun when you’re starting out.

Word choice really doesn’t matter if students understand that all words have a base element, and that we can add affixes to change or enhance their meaning. From there you can enjoy the quest of wondering, questioning, hypothesizing, and researching. Your students won’t want to stop.